|

My group aims to advance fundamental discovery in physics and the life sciences through theory led research. Beyond the traditional one way flow from physics into biology, I harness the reverse: allowing biological complexity and constraints to compel new physics. Our research agenda embraces an integrative, bidirectional strategy—treating living systems not as applications but as engines that generate new physical concepts, frameworks, and universality. Repeatedly, when biology has posed questions that existing theory could not answer, this approach has delivered genuinely new physics.

Building on these insights across molecular, cellular, tissue, and organismal scales, my programme uses precise, falsifiable predictions to drive the creation of new physics. The key strands of our current research agenda are outlined below—each rigorously motivated by biological phenomena and opening abundant avenues for novel physics. |

Intracellular Compartmentalisation

Biology: Biomolecular Condensation

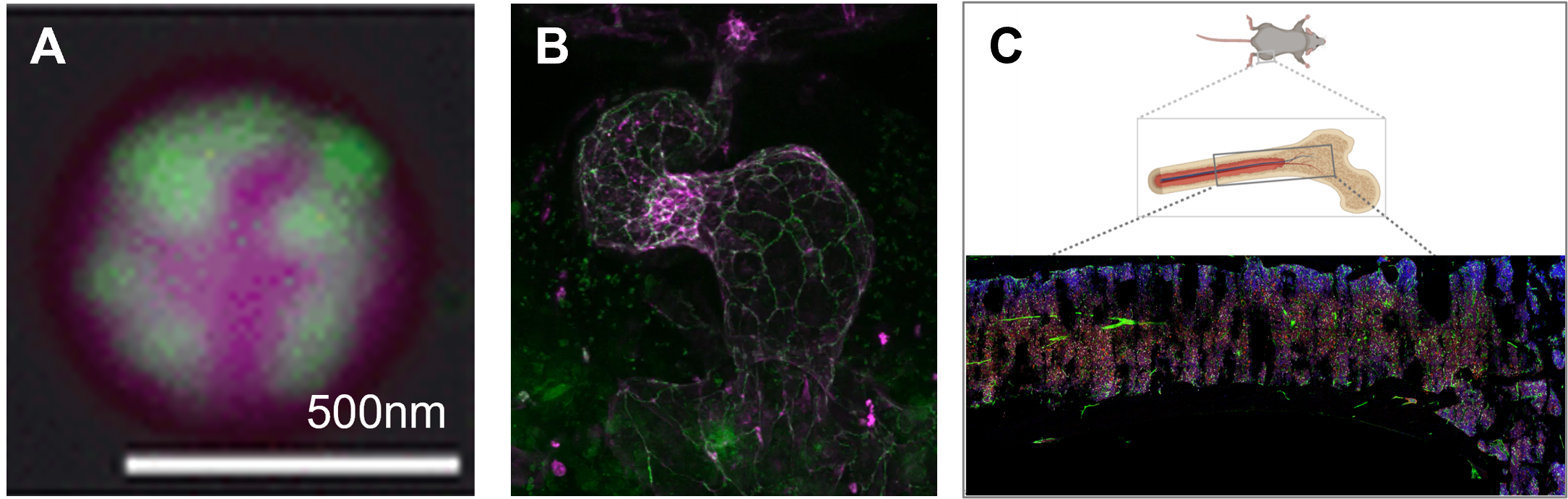

Biomolecular condensation has transformed cell biology and is now central to understanding intracellular organisation. This revolution was kick-started in Dresden, where, as a PKS Distinguished Research Fellow, I worked with pioneers to develop foundational theory of nonequilibrium phase separation regulated by protein gradients, particularly in P granules of C. elegans [1]. More recently, guided by new experiments, I helped elucidate Pickering effects on P granule dynamics in collaboration with the Seydoux group at Johns Hopkins (Fig. A) [2]. Phase separation physics also appears crucial in deciphering synapsing dynamics during meiosis in C. elegans, where emerging mechanistic models are linking biomolecular interactions to macromolecular dynamics [3].

Physics: Nonequilibrium Phase Separation

Where equilibrium phase separation is textbook physics, driven or active phase separation remains comparatively underdeveloped. Motivated in part by the P granule system, I have advanced theory in nonequilibrium phase separation [4–7], including the development of conversion-limited phase separation as a generic framework explaining slow coarsening in biomolecular condensates [8]. This work is rooted in reconciling theory with quantitative experimental data [2], demonstrating how biology can shape new physical principles.

Figures. A) MEG-3 clusters (green) coat P granules (pink) in C. elegans, leading to the Pickering effects that slow down coarsening dynamics [1]. B) Zebrafish endocardium at 48 hours post fertilisation (Vermot lab, Imperial). VE cadherin (magenta) marks cell–cell junctions; actomyosin (green) highlights the cell network, which closely conforms to a centroidal Voronoi tessellation (CVT), consistent with a universal biomechanical mechanism in epithelia that exhibit CVT like patterns. C) Schematic of a mouse long bone with a representative bone marrow microscopy field (Lo Celso Lab, Imperial), highlighting haematopoietic stem cells (red), nuclei (blue), and blood vessels (green). Ongoing experiments will map additional cell types and microdomains, enabling quantitative modelling of the haematopoiesis in the bone marrow.

Biology: Tissue Dynamics and Morphogenesis

Active matter frameworks—vertex models, active fluids, gels, and solids—now underpin quantitative studies of morphogenesis. I helped resolve a longstanding puzzle: tissues modelled as active nematics can appear extensile despite contractile behaviour at the cellular level [9,10]. In collaboration with Darryl Overby (Imperial), I also introduced an inverse bleb perspective to explain giant vacuole formation in the endothelium that regulates eye pressure, using active matter theory to account for the key dynamical features observed [11].

Physics: Active Matter Physics

Active matter matured after the surprising discovery of ordered phases in two dimensions and now anchors major areas of soft matter, nonequilibrium, and statistical physics. Because microscopic constituents generate their own stresses, the resulting dynamics are not constrained by a free energy, enabling a wealth of new universality classes (UCs). With collaborators, I have employed perturbative and functional renormalization group methods to uncover more than ten new UCs in the past decade [12–19].

Life as a Complex System

Biology: Haematopoiesis

Haematopoiesis—blood cell production—is a paradigmatic complex system that integrates hierarchical proliferation and differentiation with feedback regulation, spatial compartmentalisation, and responsiveness to physiological stress. A striking discovery in 2009 revealed that haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) actively migrate within the bone marrow, yet the functional role of this motility remains unresolved [20]. I maintain a long term collaboration with Cristina Lo Celso (Imperial) to quantify the patterns and dynamics of HSC motion and to test hypotheses for its physiological function.

We are currently developing a quantitative, data driven model of in vivo haematopoiesis (Fig. 3). Using high resolution imaging, we are generating spatially registered maps of multiple cell types and microenvironments and extracting trajectories and interaction statistics. These measurements inform a physical framework that unifies microdomain specialisation with temporal niche transitions and yields clear, falsifiable predictions about clonal dynamics, niche formation, and the consequences of perturbing motility.

Physics: Novel patterns & universality in complex systems

A comprehensive theory of haematopoiesis requires integrating active matter with nonequilibrium phase separation while explicitly allowing mass addition/removal (cell proliferation and exit of the bone marrow) and energy injection (active motility of HSC and nonequilibrium interactions among distinct cell types)—mechanisms that challenge standard physics training. This multi-faceted, driven setting naturally produces non-reciprocal interactions, emergent organization, and novel hydrodynamic variables and symmetries. We expect new classes of static and dynamic patterns at mesoscopic scales and, in the hydrodynamic limit, another treasure trove of UCs.

Broader Significance and Long-Term Vision

Recognising biology as fertile ground for new physics echoes the mid 20th century realisation that everyday materials harboured untapped phenomena—an insight that birthed condensed matter physics, now the discipline’s largest subfield. That field catalysed technological revolutions, including modern computing, and supplied foundational tools for biophysics by elucidating the structure of DNA. The biophysics I envisage—deeply tied to health and life, enabled by experimental advances that permit stringent tests of theory, and rich in genuinely new physics—can become the next “condensed matter physics.” Ultimately, uniting biology and physics in an integrative, co creative endeavour makes discovery inevitable and ushers in a unified science that reshapes our understanding of matter, life, and the principles that govern both.

References

[1] C. F. Lee, C. P. Brangwynne, J. Gharakhani, A. A. Hyman, and F. Jülicher, Spatial organization of the cell cytoplasm by position-dependent phase separation, Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 088101 (2013).

[2] A. W. Folkmann, A. Putnam, C. F. Lee, and G. Seydoux, Regulation of biomolecular condensates by interfacial protein clusters, Science 373, 1218 (2021).

[3] S. G. Gordon, A. A. Rodriguez, Y. Gu, K. D. Corbett, C. F. Lee, and O. Rog, The synaptonemal complex aligns meiotic chromosomes by wetting, Sci. Adv. 11, eadt5675 (2025).

[4] C. A. Weber, C. F. Lee, and F. Jülicher, Droplet ripening in concentration gradients, New J. Phys. 19, 053021 (2017).

[5] J. D. Wurtz and C. F. Lee, Chemical-Reaction-Controlled Phase Separated Drops: Formation, Size Selection, and Coarsening, Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 078102 (2018).

[6] J. D. Wurtz and C. F. Lee, Stress granule formation via ATP depletion-triggered phase separation, New J. Phys. 20, 045008 (2018).

[7] C. A. Weber, D. Zwicker, F. Jülicher, and C. F. Lee, Physics of active emulsions, Rep. Prog. Phys. 82, 064601 (2019).

[8] C. F. Lee, Scaling law and universal drop size distribution of coarsening in conversion-limited phase separation, Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 043081 (2021).

[9] A. Killeen, T. Bertrand, and C. F. Lee, Polar Fluctuations Lead to Extensile Nematic Behavior in Confluent Tissues, Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 078001 (2022).

[10] A. Killeen, T. Bertrand, and C. F. Lee, Machine learning topological defects in confluent tissues, Biophys. Rep. 4, 100142 (2024).

[11] A. Cairoli, A. Spenlehauer, D. R. Overby, and C. F. Lee, Model of inverse bleb growth explains giant vacuole dynamics during cell mechanoadaptation, PNAS Nexus pgac304 (2022).

[12] L. Chen, J. Toner, and C. F. Lee, Critical phenomenon of the order–disorder transition in incompressible active fluids, New J. Phys. 17, 042002 (2015).

[13] L. Chen, C. F. Lee, and J. Toner, Moving, Reproducing, and Dying Beyond Flatland: Malthusian Flocks in Dimensions d > 2, Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 098003 (2020).

[14] L. Chen, C. F. Lee, A. Maitra, and J. Toner, Packed Swarms on Dirt: Two-Dimensional Incompressible Flocks with Quenched and Annealed Disorder, Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 188004 (2022).

[15] P. Jentsch and C. F. Lee, Critical phenomena in compressible polar active fluids: Dynamical and functional renormalization group studies, Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 023061 (2023).

[16] L. Chen, C. F. Lee, A. Maitra, and J. Toner, Dynamics of packed swarms: Time-displaced correlators of two-dimensional incompressible flocks, Phys. Rev. E 109, L012601 (2024).

[17] P. Jentsch and C. F. Lee, New Universality Class Describes Vicsek’s Flocking Phase in Physical Dimensions, Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 128301 (2024).

[18] M. Wong and C. F. Lee, New Universality Classes Govern the Critical and Multicritical Behavior of an Active Ising Model, arXiv:2507.06068.

[19] G. Legrand and C. F. Lee, Universal Behavior at the Lifshitz Points of an Active Malthusian Ising Model, arXiv:2511.02566.

[20] C. Lo Celso, H. E. Fleming, J. W. Wu, C. X. Zhao, S. Miake-Lye, J. Fujisaki, D. Côté, D. W. Rowe, C. P. Lin, and D. T. Scadden, Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche, Nature 457, 92 (2009).